When I first became a writer, I quickly grew frustrated with the writing advice books available at the time. They all said a lot of the same unhelpful things, like “Just write” or “Butt in chair.”

Nearly twenty years later, I finally get the advice, but by the time you get it, you no longer need it (which, as I think about it, makes it especially unhelpful and patronizing to new writers).

But I also understand why more established writers say things like that—they just don’t know what else to say.

Writing (sitting down, thinking of something to write about, and then hammering it out in a million iterations until it’s to your satisfaction or the deadline comes around, whichever’s first) is pretty straightforward, so from that angle, “butt in chair” is useful advice. If that’s your aim for writing, then yes, you just have to make yourself sit down and do it.

But what if you have different aims?

What if you want to write in a more cohesive way, where the thing you write today builds off what you wrote yesterday?

What if you want to make a promise with your writing and deliver on it by project’s / book’s / story’s end?

What if you want to develop a process around your writing, a system that provides scaffolding to help you produce more consistently and with higher quality results?

I’m coming to see writing systems to be as personal as productivity ones.

It sounds logical, for example, to walk into an office supply store, find a pristine new planner, and have it solve all your GTD dilemmas, but if you’re anything like me, you find yourself abandoning it two months later in search of a better one.

This isn’t our fault, or even the planner’s. It just wasn’t created with you and me in mind. It was built by (and for) someone else, someone super-productive who managed to figure out how to get things done for herself, create a system around it, and then have enough people ask about her system for getting things done that she finally created a product around it.

But she designed the system for her, not the people inquiring about it and certainly not you and me.

If we’re going to have systems that work for us (as individuals, with individual preferences, tendencies, and wiring), we’re going to have to figure them out (and design them—specifically) for ourselves.

Is that to say ready-made systems and advice books are a waste of time and resources? Not at all. We have to start somewhere, and if you take parts of this system and parts of that one, eventually (with a lot of experimentation and tweaking), you’ll come up with a combination that works for you.

I think of it like Ayse Birsel’s soup analogy in Design the Life You Love. You can take combinations of ingredients and make them into a wide variety of soups, and any variation of the ingredients yields an entirely different soup. Productivity and writing systems are the same.

Instead of looking at the whole planner, for example, consider the specific elements of it and decide which ones you like best and work for you. Keep those and devise your own planner that takes into account your preferences, needs, and tastes. In the end, yours might be a combination of elements from a half a dozen individual planners, and that’s okay, so long as it helps you achieve your goals and stay organized in a way that meets your needs.

Your writing system requires individualized construction, too.

You might start by researching other people’s systems (which isn’t the easiest task, because there’s not a lot out there, at least that I’ve found so far—which is why I wrote this post!).

Once you have a few systems in mind, you have to deconstruct them and find the bits and pieces of each that work for you (or that you think might work).

From there, it’s likely you’ll have to create your own elements to fill in the gaps that exist within your in-progress system.

Finally, you have to actually use the system, test it, and refine it.

(All that before even getting to the writing!)

And here’s where that “butt in chair” advice comes in handy. You have to actually sit down and work on your system. As much as we might wish, it’s not just going to magically produce itself. But what other choice is there? Not developing a system? Writing ad hoc forever? I’d like to say that might work if you were just doing articles week to week, but I know from my own experience that it just leads to stale, scattergun results.

Here’s my current system, which may or may not help you with your own, but in case there’s even a small part that does, I thought I’d share.

Warning No. 1: Colossal brain-dump ahead.

Warning No. 2: This might be a post that requires slow digestion, so bookmark it or email it to yourself or do whatever you do to save research for revisiting, because you might want to dig into many of the resources and try things out one at a time.

Warning No. 3: This is a duct-taped, Gorilla-glued system if I ever saw one, so it may absolutely not work for you, but hopefully it can at least get you thinking about possibilities for your own system, and if you already have one, submit a guest post and share it with the rest of us!

I started the process by researching other people’s systems and the available writing tools I could find.

It was a years-long, not easy process, but here are the ones I found most helpful in developing my own system. I won’t explain each of them in detail, since they’ll make more sense reading them directly from their sources in full. I’ll just share tidbits of each, as well as—hopefully by the end—how I’ve incorporated them into my own system.

Ryan Holiday and his notecard system (inspired by Robert Greene)

Ryan’s system is, for me, where it all began. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve read his post, printed it out, deconstructed it, lost my copy, printed it again, and started the entire process over again. (In fact, I just saw my printed copy in the last week or so, but couldn’t find it when starting this post!)

I’ve always been an index card person, and that’s probably what attracted me to Ryan’s system.

While it can be time-consuming writing things down on index cards, in the end I find it actually saves time, because most of my digital or notebook brain-dumps are all over the place and need reordering and restructuring anyway. The index cards provide a way to group and stack and rearrange quickly, and it makes it a lot easier to think and make sense of what you’ve written.

My absolute only concern and complaint about index cards? Fire and searchability / findability / connect-ability.

Fire is always a concern, but I do my best to have a Zen-like attitude about it. If it happens, that writing just wasn’t meant to be I guess (unless I can remember it, which is unlikely).

Searchability / Findability / Connect-ability is the bigger issue for me.

My brain is all over the place, and although I want to write progressively / logically / linearly for the reader’s benefit (and mine when composing the writing), my general thinking and reflecting is erratic. It’s definitely not clean and compartmentalized. Plus, my work (which involves different target readers and topics) tends to overlap and cross-reference itself, so it’d be helpful if the system worked more like Wikipedia over old-school encyclopedias.

So digital wins on both of these fronts. You can backup your work, and it’s easy to search, tag, and connect your thoughts and writing, especially if using a tool like Roam, which we’ll get to later.

A caveat, I’m not above doing both (cards and digital), if necessary, in order to get the benefits of both. There have been times when I’ve started on cards and moved the work to digital or vice versa. Some projects and pieces are just a little harder to wrangle, and one or another method might be better suited for it (or, more likely, my brain is grasping it more easily using one method over another).

Zettelkasten

If you thought Ryan’s system was intense (and if you haven’t heard of it yet), Zettelkasten will warp your mind (in a good way, if you can stick with it long enough to start seeing the effects of your efforts, or so I hear since I haven’t come close to this point yet).

I’m still in the process of trying to incorporate Zettelkasten into my Roam system (more on that later). I was using it on index cards, but the searchability / findability / connect-ability thing kept bugging me. I knew there had to be a way to get the best of both (I wouldn’t be an INFJ if I didn’t want the ideal🤷♀️).

So, Zettelkasten. Let me see if I can give a brief summary.

Zettel means “paper slip” in German. Kasten means “box.” You’re effectively building a “research box” filled with all your notes to help you with your thinking and writing.

Each zettel (slip/card) contains a single complete thought (written as prose so that it’s ready to use in your writing) and, most importantly, has its own “address” so that you can find it and reference/“link” to it later (like hypertext in Wikipedia).

The system was created by the prolific writer and social scientist, Niklas Luhmann, who published 50 books and over 600 articles throughout his career, all thanks to his Zettelkasten method of organizing his thoughts and notes. (You can read more about that here.)

Roam

I signed up for Roam in February 2021 and immediately knew it would change my writing (and writing system) forever.

Until that point I’d been using Scrivener, and while it worked okay(ish) for me at the time, it was also clunky and had way too many bells, whistles, and unused components, making it a cumbersome program that was only available on my one computer (not online) and that effectively “locked” all my writing inside it (I still have writing I haven’t recovered from older computers and versions of Scrivener). While you could technically export your work, after experimenting with many other software options, I knew there were easier and more seamless ways of working.

What appealed to me about Roam was the idea of “networked thought,” software that worked more like your brain, which is not at all linear. The second I used it, I was sold.

(Disclosure: I’m not a Roam affiliate, but Roam Research peeps, I’m happy to be.)

It took me a minute to break old and forced patterns of thinking (hierarchies, folders, files, and separate pieces) and embrace a more stream-of-consciousness way of writing and note-taking. (For those who are familiar with Roam, it took me until this year to finally start using Daily Notes!)

I’ll admit I’ve stopped and started with Roam many times over the last three years, but (and this will especially ring true for INFJs) it just makes intuitive sense.

Like my husband and I say, we’re always having twenty conversations at the same time (he’s an ENTP), and that’s how my brain works, too. I may be writing about systems at the moment, but I’m reminded of fifty other topics as I’m going, as well as ten things I want to remember to write about later. Roam gets this and is built to capitalize on it.

But that doesn’t mean old, forced-upon-us habits die easily.

The “good student” in me wants to force hierarchical structure like she wants to avoid using and, or, and but to start a sentence (as if some condescending biddy of an English teacher is standing over my shoulder criticizing and controlling my writing output and process!).

Here’s the great thing about writing in the days of the internet: You can do things your way and find a thousand true fans who are going to love it (and that’s really all you need; see here). So you do you, boo, and forget about your English teacher!

Eva Keiffenheim and Zettelkasten + Roam

Apparently Eva’s researching and writing complaints were similar to mine: Notes everywhere—in the margins of a thousand books, scattered among stacks of articles and pages of journals, highlights stuck on Kindle, everywhere (and Lord help if you want to find a specific one—see you back here in three hours, empty-handed)!

That brings up the problem with index cards again: searchability / findability / connect-ability. Yes, tagging and addressing helps, but technology can do some of this heavy-lifting for us. I’m still in the big middle of incorporating this into my system, so it’s not at all a habit for me yet, and I’m still trying to figure out how to make it work.

One example, I haven’t quite found the reason for addressing notes, like you would with Zettelkasten. (I’m going to reread Eva’s article now that I’ve been writing this way for a bit and see if I can figure that out. I’ll report back if I can figure out why it’s necessary—or share your thoughts if it makes sense to you).

Another issue is that I’m bad about adding tags, as it takes me out of flow with the writing itself. I’ll have to find a process for this, as well as with numbering and indexing.

Note: Eva’s was the first Zettelkasten + Roam system that resonated with me, but if you search the terms, there are others that might be worth investigating, purely for the tweaks that might come from each to maximize the effectiveness of your own system.

STILL NEED: Snippet/Avocado

Eva uses ReadWise for web clipping and Kindle highlight syncing, and although I can’t remember now why I wanted to test Snippet and Avocado before going back to ReadWise—I’ve used it before—I’m going to trust my previous decision and start there. (If I ever remember why I made that choice, I’ll post an update.)

Until now, I’ve been manually adding Kindle highlights that I email to myself because of truncating. Plus, I don’t want all of my Kindle highlights automatically synced to Roam. This may sound counterintuitive, but I’m with Ryan and Robert Greene on this one. When I go back through a book, I want to be way more discerning with the highlights that make the final cut. When I’m reading a book, I’m highlighting and underlining all over the place, but on second pass, I remove a lot of them, since I usually find them much less compelling and/or relevant.

Either way, I’d like to at least experiment with snipping tools again, since it may streamline and automate the process (especially if it can delete things I unhighlight; not sure if that’s possible with any of the apps, but if one of them can, we might have a winner).

STILL NEED: Podcast/Video clipping tool

I’ve been doing these manually, too, for the same reason as with book highlights. Anytime I relisten to a video or podcast, it’s always much less relevant or compelling than when I first heard it. Usually those one-liners that stood out in the first place are the only ones worth keeping, so a manual process works just fine for me.

This brings up a good point: Do what works for you on this entire thing, including note-taking and highlights. I can see the benefit of taking copious amounts of notes, especially digitally since they can be searched, but I can also see being selective. I feel like I’m a little of both. On the front end (while reading), I’m highlight-crazy. The same goes for my notes and journal entries; there’s a lot of excess, but then I go back and cull, reducing them by as much as 80-90%.

David Sedaris and Austin Kleon on notebooks

So in January I tried, I swear I tried, to do Austin Kleon’s notebook turducken. At the end of the year, I bought four or five journals specifically for the purpose. Sadly, it didn’t last long. Maybe to February? (Maybe.)

But, now that I’ve had a month or two to reflect, I can see the benefit of at least one of the notebooks in the stack (for me, that is): the reporter’s notebook. (In fact, I’m stopping right now to go dig it out of the file box where I keep paid bills or whatever else I might need to reference sometime, but never do, and where I stuck all the notebooks by the beginning of March.)

The purpose of the reporter’s notebook? In Let’s Explore Diabetes With Owls, David Sedaris says: “You jot things down during the day, then tomorrow morning you flesh them out.”

In a given day, you might have something funny happen or overhear a phrase you want to remember or an interesting bit of dialogue, doesn’t matter. You jot it down in your reporter’s notebook that you carry with you everywhere, and the next morning, you sit down and go through the stories and snippets and elaborate on them in your journal. Any interesting stories get noted in an index you create within the journal so that you can easily reference them later.

On that note, now that I’m using Roam more deliberately, I can see using David’s index there, too, which he says “leaves out all the mumbly stuff and lists only items that might come in handy someday” (pieces he thinks might be entertaining and that he could read aloud to his audiences). He says, “Over a given three-month period, there may be fifty bits worth noting, and six that, with a little work, I might consider reading out loud.”

Austin goes into greater detail about the writing process itself. I especially like David’s way of writing and developing his work (Emerson’s way, too, I believe): journal > essay > lecture > book. Really, though, we should back it up even one more step and include the reporter’s notebook (so reporter’s notebook > journal > essay > lecture > book). You simply choose your (and your audience’s) favorite pieces in each step of the process, developing them further and further as you go.

If you’re interested in Austin’s journals, he’s the man to see. I just wish I had his discipline. Maybe one day. The “butt in chair” thing.

Rob Fitzpatrick and Write Useful Books

Rob Fitzpatrick wrote Write Useful Books, and although I loved the entire book, the one piece of advice that stays on my mind is this: “Make a clear promise and put it on the cover” (or, in the case of articles, in the title). I don’t always live up to this rule, but when I do, there’s nothing else that focuses the writing better.

I have a Rob Fitzpatrick “Write useful books” cheat sheet I created for myself, which includes four of my favorite points he makes in the book:

“Make a clear promise and put it on the cover.”

“Decide who it isn’t for. Define and defend what [it] isn’t.”

“Fill your TOC with takeaways. (What is the learning outcome or takeaway for each chapter? Each chapter and each section within it should name a specific outcome.)”

“Teach the book to test its contents.”

When it comes to effective writing, this is the advice I try to follow: What is the promise I’m making, and did I deliver on it by the end of the piece?

The Struthless plan

So I have not fully incorporated every one of these ingredients, but I found the breakdown so helpful I thought it worth adding to the mix (for you, if it helps, and for myself when I read back through this post at some point).

You can find the full explanation and list in the video here, but the specific part I’m referencing is a list of ingredients for achieving a goal (in this case, writing a book).

“Clear concept: Define the central idea, theme, or premise of your book. Make it as specific as possible.”

“Outline: Break down your book into chapters or sections. This is your roadmap, and it’s crucial.” 👈 This is no joke. The fastest thing I’ve ever written (and one that I like most) started from a quick mind map of ideas I wanted to include in the book. With that in hand, I sat down and quickly wrote the entire thing. (You can find that here; I read it every now and then for motivation. It’s called The Chicken Sh*t’s Guide to Conquering the Planet.)

“Word count goal: Estimate your book’s total word count and divide by the number of days you plan to write.”

“Daily writing quota: Based on your word count goal, decide how many words you need to write each day.”

“Time allocation: Carve out a daily writing slot. Could be as little as 30 minutes, but it’s your nonnegotiable appointment with your manuscript.”

“Weekly review: Set aside time once a week to review and adjust your outline and writing progress.”

“Support system: Identify a babysitter, a supportive partner, or a daycare service to help manage your time.”

“Accountability: Find a writing buddy, coach, or join a writing group to keep you honest.”

“Tools: Choose your writing software, note-taking apps, and any other tools you need to stay organized.”

Again, I still need to incorporate many of these into my own system. For example, without word count goals and daily writing quotas and slots, how will you make consistent and deliberate progress toward your writing goals? (Answer: You won’t. Before you know it, six months will have passed and you won’t be a word into your book, assuming that’s the goal.)

Google Docs, Nuclino, Substack

So far, when it comes to polishing articles for publishing, I’m not crazy about working in markdown within Roam. I’m a much more visual person and need to see how things look in addition to how the words sound.

So once I get to a certain point in the writing/editing process, I have to move out of Roam and into another app in order to format the post for publishing, and for this, I’ve been experimenting with (and alternating between) Google Docs and Nuclino.

I’ve tried a lot of different writing software, but I’m never so impressed that any of them stick.

There are two criteria/wish-list items for me when it comes to the “polishing/formatting” component of my system: (1) I want to format in a WYSIWYG editor, and (2) I’d like to keep my version histories synced.

For now, I’m just editing to a point within Roam and then copying into Docs, Nuclino, or Substack to polish, depending on how close I think it is to the finished piece (if it’s close, I’ll go straight to Substack).

This isn’t perfect, however, because I still make content edits even within Substack, so a more ideal process would be for me to then copy the finished piece into Roam. (I’m sure it’s possible to set up a zap to do this automatically, but that’s just one more aspect of the system that needs to be refined.)

With the start of a system in place, now I focus on testing, tweaking, and adding my own elements to fill the gaps.

One of the biggest things I’ve learned that works for me is to “have a vessel” (for everything).

A vessel is simply a container.

A container gives you a place to put things.

It forces things out of your brain and into the physical, which I think, for INFJs especially, can be a sticking point with our work and writing (if it’s just floating around in our heads, we never make it exist in the physical world, which is what we’re aiming to do). The vessel provides a physical place (virtual places count) to begin moving things out of your mind and into another reality (our ideas may be just as “real” to us in our minds, but we want them to be real to others, too, so we have to move them into an exterior reality).

I’d like to say I figured the idea of vessels out on my own, but that’s probably only partially true.

I’ve done web design and launch strategy for entrepreneurs and creatives for the last twenty years and over that time have learned just how much websites (one type of vessel) help with thinking through creative projects and businesses.

The website becomes a tool that helps clients get clear about what they’re offering, to whom they’re offering it, why they’re offering it (and why to that target person or group), and how they deliver it.

We create “a place/vessel” to put all of that (a website) and then walk the client’s prospective users/customers through it in a logical and sequential way, leading those users/customers to whatever “next step” we want them to take (buying a product, setting up a consultation, etc.).

The vessel (website) is why it all comes together, just having a place to put everything. It really helps the project come to life.

The other reason I think I know about vessels is by osmosis.

At about the same time I started doing websites, I read Twyla Tharp’s book The Creative Habit.

In it, she says, “Everyone has his or her own organizational system. Mine is a box. The box documents the active research on every project. The box makes me feel organized, that I have my act together even when I don’t know where I’m going yet. It also represents a commitment. The simple act of writing a project name on the box means I’ve started the work. Most important, though, the box means I never have to worry about forgetting. I don’t worry about that … [it’s] all in the box.”

For Twyla, the vessel is a banker box, and everything she’s ever worked on has one.

It might seem simple, but having a vessel is something I’ve very much come to believe in and depend on. Here are mine for Maison d’Evangeline and the writing.

The Maison d’Evangeline house. As Maison d’Evangeline started forming in my mind, it took on the shape of a bookshop. No, it wasn’t a real bookshop (yet), but it helped me to treat it seriously by giving it walls in my mind. I went so far as to find an actual house in the Garden District of New Orleans that looked similar to the illustrated version I’d been using as its logo. I mapped out the rooms, which we’ll get to in a minute, and even went through the real-life house’s virtual tour (it had been for sale once), in order to envision it completely in my mind. Now, when I think of Maison d’Evangeline, I see that house, and I see New Orleans (I’m from Louisiana originally, so it holds a special place), and I know its vibe, no matter where I am in the world or what the vibe is around me. The visual (especially for an INFJ) makes it “real” to me, and I can work with that.

The Maison d’Evangeline rooms. Once I had the house in mind, I needed a “floorplan,” and this was less about the actual real-life layout and more about “what do you do here.” For me, the rooms became the categories of the Maison d’Evangeline content (Care of the Soul, Essence, Resistance, etc.), and my job and goal then would be to “build” each room, one by one, until the entire house was complete. So what kind of content would I need in the “Care of the Soul” room? And would it just be books or courses and podcasts, too, for example? The rooms gave me another visual. The house is empty and ready to be filled. People can come and visit still, but they’ll find a mostly empty house for now, but as time goes, they’ll see the rooms starting to come together. On top of that, this visual reminds me that, just like a house that I’m building and filling, it won’t happen overnight and will take working a little at a time.

The Maison d’Evangeline website. The website “vessel” helps me “hold it all together.” It becomes a physical representation of the vision in my mind and reminds me where I am in the process. It also serves to remind me of things like the mission and focus of Maison d’Evangeline. Anytime I’m feeling a little bit lost with the project, I can visit the website and quickly get my bearings.

The clubs. Having the clubs at Maison d’Evangeline allows me to further subdivide interests and groups within Maison d’Evangeline. Just as with a real-life bookshop, the club concept is easily understood and doesn’t detract from the overall shop, mission, or focus. Plus, clubs are a little less intensive and formal than the overall project, so they provide structure and space for things without being overwhelming or drowning out the shop and its content. As an added bonus, they provide a way to explore more temporary interests or to even test ideas before engaging in them more fully. Having the clubs also provides a way to stay on top of particular interests and content, so with the INFJ writers club, for example, it reminds me that I am both of those things and have members who want to be more successful and serious about those two aspects of their lives, and every two weeks I have a promise to keep (even if I’m a little behind sometimes!). The commitment keeps that part of my life (and hopefully your life) top of mind, and even just focusing on it twice monthly is better than nothing at all.

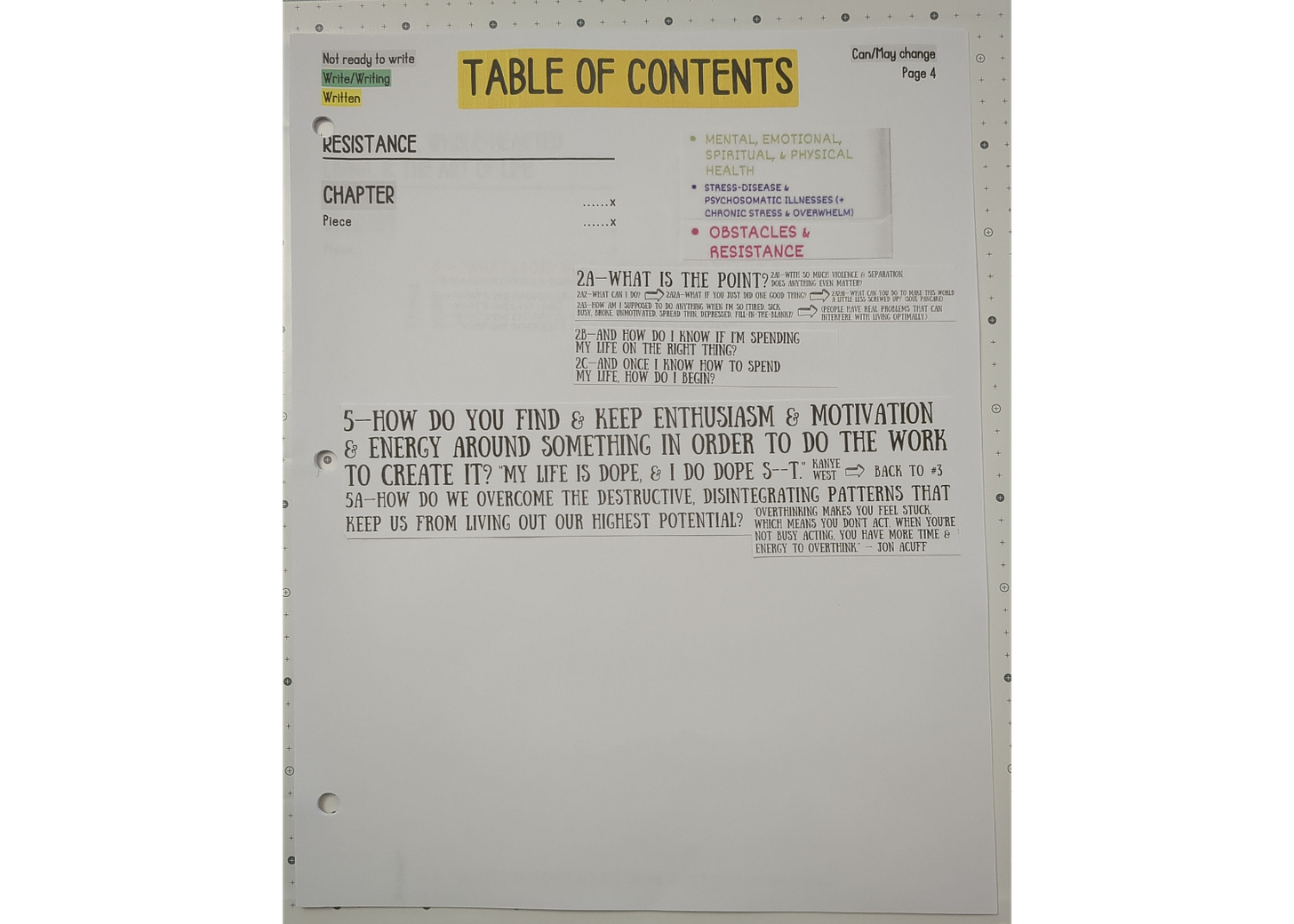

A binder for each project. A project (for this particular purpose) is something like a book or course that has multiple pieces (essays, articles, etc.) within it, so anything that requires a table of contents maybe. I currently have only one project going, and I haven’t even assigned it a name yet. For me, a big component of Maison d’Evangeline is answering “life’s big questions,” and I’m constantly compiling lists of them (see image below). When I started thinking I wanted a more deliberate approach to the content at Maison d’Evangeline (overall, not within the clubs), I took two of the main graphics I had (images below) and cut them into pieces of individual categories and questions. Then I sorted them into a more logical sequence (the TOC for the Maison d’Evangeline project, whatever it ends up called). All of that went into a binder so that I can see how it needs to be filled in (see terrible TOC scan attached—one page of it at least).

A bin, basket, or cart for each club and/or project. Like Twyla with her banker boxes, I like to have a container for holding books, notes, articles, etc. related to each piece, club, or project. If it’s a small-scale something, it might just get a bin on a shelf in my office. Bigger projects might get a 3-tiered cart. I usually don’t decide this in advance, unless I expect it to be a certain size. Instead, I just rearrange as necessary, which can be a pain, but forces me to go through finished or forgotten things that need to be tossed or archived. I use baskets and plastic containers with lids for sorting things, too. Some of them contain stacks of books I’m using for research for one bibliotherapy piece or another. Others may hold notes and planning materials for newly developing projects. These aren’t strictly for writing. Some might hold temporary files and notes for different business or life projects, too. Having these vessels brings some (slight) level of order to my office space, too. When the piles start accumulating around my desk area to the point that it’s hard to see around them or move anything without causing an avalanche, I know it’s time to send everything home (meaning, back to their respective bins, baskets, and carts).

A book lists and stack for each project or piece (in baskets, in bins, and on Kindle). I also keep carts of books that are sorted for particular pieces or projects or groups of them in crates, bins, and baskets. Usually I start with a list from Kindle and then go around the office and house gathering relevant hardcopy books to add to the list. The lists are kept in the notes or binders for each piece or project. I usually start with the list, looking for the books I suspect will be most relevant, and then I’ll locate their physical copies from the sorted stacks. This makes the research process easier, since I can pick what I’m going to work on for a given day or time period, find their relevant vessels and move them near my desk, and then settle in for a long work session without having to stop to locate books, resources, and materials.

And that’s it. The vessels, as simple as they might sound, provide an external “living space” for all the things dreamed up by an internal-living INFJ. (Otherwise, they’d just stay in my head!) As soon as I know I want to make something real, I know it needs some sort of vessel (or two or three). Once it has a vessel, it starts to come to external life.

As for filling in the rest of the gaps in my system, well, I’m still trying to figure out what those are, so I’ve started paying attention to my writing flow in hopes of discovering where there are areas of friction or “stuckness” that need to be addressed.

Here are the rough phases of writing I have (specifically for bibliotherapy).

Phase 1: Inquiry

Step: “Scratching”

Scratching is another Twyla Tharp term.

She says, “The first steps of a creative act are like groping in the dark: random and chaotic, feverish and fearful, a lot of busy-ness with no apparent or definable end in sight. For me, these moments are not pretty. I look like a desperate woman, tortured by the simple message thumping away in my head: “You need an idea.””

“Scratching takes many shapes,” she explains. “A fashion designer is scratching when he visits vintage clothing stores, studies music videos, and parks himself at a sidewalk cafe to see what the pedestrians are wearing.”

I described my process for scratching in the most recent Bibliotherapy club article.

This part of the process is brutal, and I’m not sure there’s any way around it or to make it less messy.

The most important thing, as far as I’ve been able to tell, is to be sure to capture your ideas while scratching, which is why I usually start the process in my journal. If I come across something that would be good for a future piece, I try to highlight it some way so that I don’t lose the insight. I could see where this could slow you down, though, so some people might consider lost insights to be the price of admission for a particular piece.

Step: Finding the question/promise

An extension of the scratching process is zeroing in on the question I want to answer or promise I’m making for a specific piece. I usually gauge this purely by my own interest in getting the answer or solving the problem.

Also, I’ve been forcing myself to actually state the question or promise, because (a) it focuses the piece and (b) it helps fill in the TOC and binder (see previous section on vessels).

Phase 2: Input

Step: Research

This is another messy process. I usually start by searching out key terms from the question or promise (Phase 1) in my Kindle and Amazon book purchases, and when I’ve exhausted that, I just start browsing (Kindle and physical book shelves), making a list of all the potential resources that might hold keys to the answer or solution.

The final list may be one hundred books sometimes, so I highlight the most likely suspects and dig in, making an archive of notes as I go (until very recently I did this on index cards and in notebooks, but I’m trying to move to the Zettelkasten + Roam method).

Step: Archiving

What follows are the different types of Zettelkasten notes I take within Roam during the researching and archiving steps.

Fleeting notes

You can think of fleeting notes like scratchpad notes. They’re just there to remind you to look into something else, write about something, etc. They serve more as to-dos/reminders than actual notes within your files. Still, you need them so that you remember random insights and rabbit holes you might like to explore at some point.

If you’re using Roam, a good way to gather these in one place for processing at some point would be to tag them (examples: #toDo #toResearch #toExpand). You can then go to that tag/page and find/process them all at once. The main thing would be to actually process them, so it’d probably be a good idea to review these items periodically (see Struthless and/or Sedaris above).

Literature notes (or in my system, Source notes)

I call Literature notes “Source notes” since that makes more sense for me, especially nowadays with so many different types of media sources, where you can learn just as much from YouTube as you can from a book. I use any and every type of source, including conversations, and “Source” makes more sense to me, in that case (as in, “What was the source of this?”—it reminds me there should be one and to cite it).

Source notes are just that, highlights and information that need to be attributed to someone else.

In Luhmann’s Zettelkasten system (and in many other people’s if you search online), these notes are written in your own words, but I prefer to note direct quotes (in quotation marks so that I know they’re from someone else). This is just a personal preference so that I don’t have to look up someone’s exact words later, and I have a weird compulsion of not wanting to put words in someone’s mouth.

Within your source/literature notes, you’re going to tag them as such and also cite the source. Eva’s article above includes good templates for this.

Permanent notes

Permanent notes are your own writing/thoughts (one per note/card—or bullet, if you’re using Roam).

The way I like to think of it is that you’re studying certain branches of knowledge that interest you or that encompass your work (or, ideally, both), and if this is your work (or you want it to be), then your goal (whether you get too public/big with it or not) is to become a thought leader within the topic (or topics). In that case then, you’re researching, learning, and forming your own opinions, thoughts, insights, and theories about these topics. Those things become your permanent notes, and over time, those notes become your body of work (you’ll take them and combine them into arguments and pieces: reporter’s notebook > journal > essay > lecture > book OR courses OR whatever).

Permanent notes, just like your opinions, aren’t set in stone. They can evolve and change over time (and that’s more writing for you and your body of work, to explain what made you change your mind; nowadays we could use more of that!).

Step: Retrieval

This is a big friction point for me right now, and I think it’s because it’s another “butt in chair” moment: there’s no way around simply (not easily) sitting down and slogging through the work, which means reading and rereading your own notes and deciding what’s relevant to this particular piece or work.

Part of the friction for me, I suspect, comes with the tagging part, and like fleeting notes, there probably just needs to be a process and set/regular time frame for going through and tagging previously created notes.

One thing I have been doing—and where I might be able to add this step of the process—is adding certain tags, as well as a word count, at the start of each piece within Roam (screenshot), so for example, at the start of this article, I have the following tags: #[[INFJ writers club]] #[[Notes on writing]] #[[the INFJ writer]], which lets me know where this piece will likely be published, as well as what else it relates to (example, notes on writing). I could easily add a #toTag tag so that I can locate pieces that need to be tagged. This doesn’t solve the problem for individual notes, but if done at a regular slot/interval each day/week, that might take care of those, too.

Phase 3: Output

Step: More “scratching”

Scratching might not be the most accurate way of describing this part of the process, but it’s basically the point where I have all the information (or enough) to begin, and it’s time to start massaging it all into something.

Sometimes this is as simple as (again, simple but not easy) finding the heading and sub-headings of a piece. It could also mean deciding how to format it (this is often the case with Bibliotherapy club pieces, since there’s a very informal/messy feel to the work there).

This is another uncomfortable / chaotic / procrastinate-y / “butt in chair” part of the process, where you’re trying to figure out “What is this thing?” You know that you’ll eventually get it (probably), but between here and there are miles of nothing fun.

Step: Rhythm

There comes a point, although you usually don’t realize when you arrive at it, when you’ve found your groove with a particular piece. You’re moving things around, typing furiously, and things are coming together.

From here, it just becomes an increasingly tiresome loop (at least for me) of typing, moving, rereading, rearranging, typing some more. With each pass, I inhale a little deeper in frustration and/or exhaustion. This can go on for hours or days or weeks, depending on the length of the piece, and can be especially draining since it (again, for me) seems to take a lot more energy and brain power than other steps.

And I can never tell how long I have left, how many more rounds of rereading and tweaking. There usually just comes a point when I know it’s as good as it’s going to get for now. If I put it aside for some period of time, weeks or months maybe, I could come back and adjust a few things, but for now, it’s done.

That’s the line for me between my own personal best and perfectionism, excellence (at least for where I am right now in my abilities as a writer) and perfectionism.

Sometimes I can’t tell that I’ve crossed the line until some amount of time later when I jolt out of the trance and tell myself, “Enough already, now you’re just picking at it—it’s good!” This is a hard thing to navigate as an INFJ. Perfectionism and shame are our game, and editing is a process of running through something over and over again until it’s as right as it’s going to get—but, without crossing over into being obsessive and compulsive about it. A fine and faint line.

What’s missing?

Phase/Step: Cleanup/Archiving. Definitely. Tagging. Categorizing. Copying finished pieces back into Roam. Putting finished pieces into the binder (see vessels section above), if they belong there. I don’t even know what else should go here, but what I do know is that a lot of my writing (a lot, like hundreds of thousands of words) is scattered over a half a dozen places or more and, if gathered together in some cohesive way, would be doing me a lot more good than sitting in some notebook, folder, or server somewhere. But I’ve always been terrible with cleanup/archiving. This is probably an INFJ thing, too, although I haven’t given much thought to it, so I don’t know how or why.

Now, as I said earlier, my system is a work in progress. I can’t imagine ever getting to a point where it’s 100% complete, and every few years I tend to go through all my old notes, writings, and files and can easily see how my system and writing have evolved. Even over the course of a single year, depending on the circumstances, things can change quite noticeably.

Also, I revisit books and systems that have helped me establish my own system every few years, too, at a minimum. I find with learning that I absorb things in layers, starting with the broadest strokes. If I tried to incorporate everything, I’d quickly get overwhelmed, so I don’t even try. I pick the elements that make immediate sense and that will offer the fastest results. Then I revisit the system again and again, taking on additional layers of it until I’ve gotten as much use from that system as I’m able. (Note: I’ve found this to be a really important step, as I consider the author of the system a “power user” of it, so there are likely a lot of nuances to it that will refine the workflow, if I can incorporate them eventually. Plus, some things just won’t make sense at the start, but will the longer you use it.)

And as for all that writing advice (“butt in chair,” “just write,” etc.)?

If you’re a new writer, unless you learn much faster than most people, that kind of advice will be infuriating for a while. It comes from experienced writers who’ve learned (over a lot of time, trial, and error) that you can’t get away from the difficult aspect of writing and creating, which is just sitting down and facing the fact that you have no idea what you’re about to do and if it’ll be worth anything or how you’ll do it or if anyone will want to read it and if it’ll be criticized and if it’ll be a waste of time that’ll end up in the recycle bin.

At some point, every writer who sticks with it figures out that you just have to sit down and force yourself to stay there (and do nothing else—NOTHING!) until you start and finish the work.

So if you are a fast learner, take that advice to heart, even if your brain wants to say, “No, shiitake mushrooms, butt in chair! But then what?!” Every other writer and creator is wondering the same thing, every single time he/she/they sit down to create.

Eventually you learn to not be scared off by it. Or bored off (is that a thing?). It’s all part of the process (or system).

Anyway, I hope this 8k+-word post helped even a little with your writing process, and if you’ve figured out some handy writing system hacks, please share! Inquiring and tortured INFJ writing minds want to know!

Until next time!

A.

Great read for an INFJ writer 😃! Thank you! I use Scrivener too, but for me it’s like driving 10 mile an hour in a Ferrari. I also use Notion for saving ideas. Do you know that one? It helps me to categorize all my micro-obsessions. I really love the images of your brain dumps!